I am driven to write on this topic in answer to the many readers who have finished The Dragon Heir, the last novel in the Heir Trilogy. Some have written to take me to task for killing off one of the major characters.

One reader wrote and said,

I will admit that when ___ died, I started crying. I actually had to put the book down for several minutes, because I was crying so hard.

Another wrote and said, You did NOT have to do that.

Some readers said they were totally blind-sided, and others that it was totally predictable. Several questioned whether the character’s death was faked and suggested there might be another book coming in which he/she might be resurrected.

To be fair, not everyone agreed that the death was a mistake. One reader described the ending as absolutely perfect. Another wrote to say that I had not killed off ENOUGH characters and had a list of a few more I could have offed. (Should I worry about this reader?)

It’s fairly common that characters are killed in books and movies—but they’re usually minor characters. There’s even a term for dispensable characters that came from the science fiction series, Star Trek—“red shirts.” According to Wikipedia, “A redshirt is a

stock character, used frequently in

Star Trek, whose primary purpose in the

plot of a story is to die soon after being introduced, thus demonstrating the dangerous circumstances faced by the main characters.” The security officers wore red shirts, you see, and generally didn’t survive planetary landings. The main characters—Kirk, Spock, Scotty—survive major battles time and time again.

In the westerns of my childhood, main characters always ended up with their arms in a sling, to demonstrate that they had not escaped completely unscathed.

Killing off major characters is not a new thing. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle famously killed off Sherlock Holmes in The Adventure of the Final Problem, published in The Strand magazine. According to The Chronicles of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, (

http://www.siracd.com/work_h_death.shtml) more than twenty thousand enraged fans cancelled their subscriptions to the magazine. After considerable pressure from readers, Conan Doyle eventually brought his detective back to life in The Adventure of the Empty House.

Supposedly, J.K. Rowling wept when a character died in Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix. Neither did she enjoy killing one of her favorite characters who died at the end of Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince. More deaths followed in Deathly Hallows. So it seems reasonable to ask—why did she do it? Why does any author kill off the characters they brought to life on the page?

I recently attended the World Fantasy Convention in Calgary. There was actually a panel on killing significant characters, including authors Tad Williams, George R.R. Martin, and Steven Erikson. Martin, especially is known for the ever-expanding body count of main characters in his most recent fantasy series.

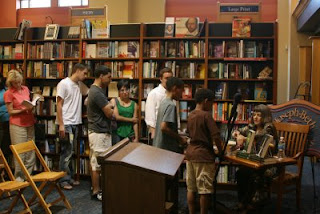

TAD WILLIAMS AND GEORGE R.R. MARTIN

World Fantasy Convention, Calgary

Martin makes no apologies. In fact, he says, Gandalf should have stayed dead in Lord of the Rings, because he was the man with all the answers, and the Fellowship should have been left on its own. Erikson argued that it’s all right if dead characters come back, if they come back as different people—transformed by their death experiences.

Williams surmises that you’re seeing more deaths of significant characters these days because modern speculative fiction seeks to be more realistic. But, he said, the death has to have some impact on the story. Erikson agreed. “If it’s a random death, people tend to get really pissed.” Martin argues that it’s unreasonable to think that in a story filled with violence and clashes of arms that no named character would die.

During the Q&A at the WFC panel, I asked the panelists how they respond to reader complaints about the deaths of significant characters. “I tell them to quit complaining,” Tad Williams said, “or I’ll kill them all off.”

He was joking. Really.

So—about Dragon Heir. It’s hard for me to explain my rationale for the choice I made in DH without major spoilers, so—spoiler alert!! Read further at your peril!

* * * * * * * *SPOILERS BELOW* * * * * * * * *

Many of the reasons cited by the WFC panel underlaid my decision to have a major character die near the end of DH. Death is what happens in wartime, and the Weirguilds are involved in a war. I knew it was going to happen, and to whom, from the beginning. That is one reason it was important to have two viewpoint characters throughout the book.

About Jason—Readers don’t seem to believe me when I say that Jason Haley is one of my favorite characters. He was so flawed, so human, so edgy and full of self doubt. Jason’s fate had a lot to do with his personality and his desires—it wasn’t random. He was reckless and careless and had a kind of death wish in him. He took chances—life for him was a series of dares. He could never see how important he was to the other characters in the story.

What Jason wanted most in life was to make a difference. And he did. He saved everyone by letting go of the Dragonheart and getting Madison where she needed to be. He was the only one who understood that Madison was the key. And he saved Jack and Ellen by killing D’Orsay. It was revenge, but there was an inevitability about it that made sense to me.

Do I have any regrets? I wish that Jason and Leesha had had a final scene together—some kind of resolution. On the other hand, it seemed to me that Leesha had to pay a price for all the terrible things she’d done. And she did pay a price. It was life-changing.

I also wish I’d spent more time on the denouement. The grief scene in The Fellowship of the Ring when Gandalf was killed recognizes and highlights the importance of the loss. The ending of DH seemed abrupt, my readers tell me.

* * * * * * * * *END OF SPOILERS* * * * * * * * * *

That said, any rationale for killing off a character seems like an excuse for a cold-blooded decision. You killed him off to prove a point, didn’t you? To teach a lesson. To raise the stakes. To tug at the reader’s heart strings.

You killed him off because that is what the story demanded.

That last is the only reason that matters. And the argument can go on forever about whether that applies here.